YIANNIS ISIDOROU: WHAT ASGER JORN [UN]/TAUGHT ME – A TEXT OF 11 POSITIONS REGARDING THE MOVEMENTS AND TROPES OF THE ARTIST IN THE SYMMETRICAL(IZED) WORLD OF ECONOMY

Within the framework of my research into Asger Jorn´s writing and thinking I organize public and semi-public sessions with special guests at a variety of venues. The guest´s practice, knowledge, insights, or responses are informative to my research, or steer the direction I take on a particular topic. The sessions also often respond to the context of the hosting institution, or to a specific request. Making the sessions public is a way to share and enter into a dialogue with the audiences.

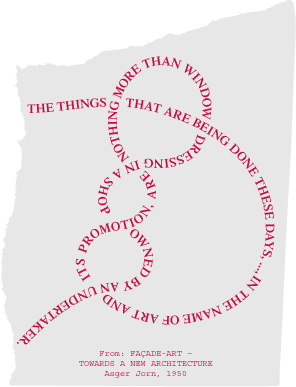

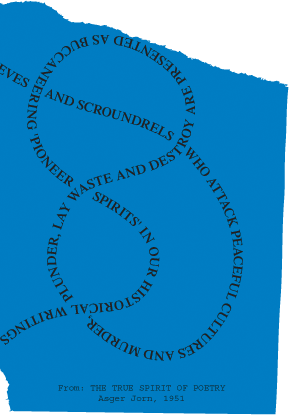

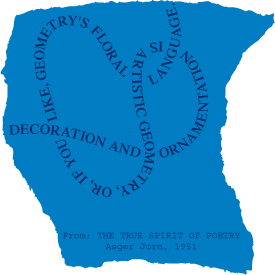

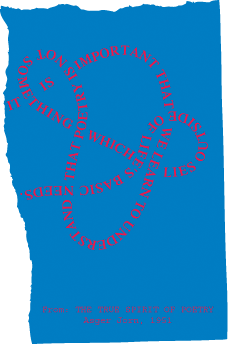

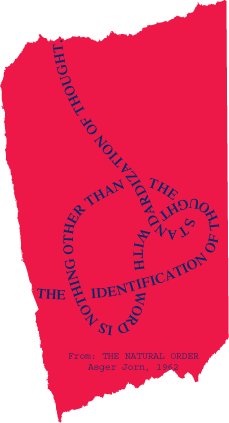

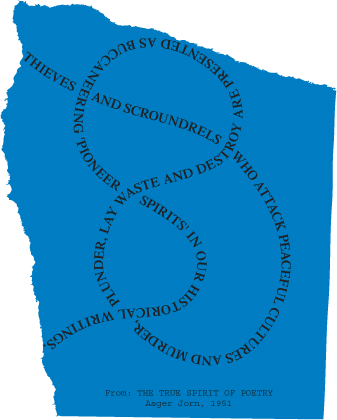

On January 8, 2016 the session ‘Asger Jorn: Thinking in Threes’ was hosted by Circuits and Currents, the Project Space of the Athens School of Fine Art. Two Athens-based artists contributed to this session. Kostis Velonis with the text ‘Alfred Jarry and Asger Jorn: the Epicurean Influence as Social ‘Swerve’ which can be found in the Pataphysics section of this blog, and Yiannis Isidorou with the performance-text below, which consists of a compilation of Jorn citations, partly shifting the original intentions as “to point out some extra risks of today”, to speak with Isidorou.

Yiannis Isidorou’s practice spans a broad range of media including photography, video, sound design and installation. He is co-founder and editor of the Greek e-magazine happyfew.gr on politics, philosophy and art. In 2004 he established Vortex Studio an independent art space and seminar center where he teaches photography and video. His latest project, another co-operation with Yiannis Grigoriadis, called “Salon De Vortex” is a thorough research on democracy, dominance and decay in the post war european society.

1.

Modern science makes us understand the true character of the machine, of rationalization and of standardisation. All of that leads to one thing only: the economy. Economy attempts (is) the symmetricalisation of forces.

Art is to create inequalities.

It is a way of breaking with common taste but also, of reconceptualising it by means of that break, it is a strategy of redescription and re-presentation , a process of hi-jacking. Criticism and affirmation coexist. Imagination, game, awareness, contingency, subversion of the existent.

Every conscious creative act concerns itself with the boundary of self-interestedness and aims at its rapture and containment.

2.

I remain unpredictable at every moment, create the preconditions for surprise and disturbance, I manoeuvre amidst the multitude.

The artist is a chameleon. Lives as the servant of the contingent and the infinite. Bases his cause on nothingness. Moves across the surface, to the margins or even beyond the space defined by consensus, ideology, the common view of things.

Art is not a standard of behaviour but a field of experience.

3.

The reconfiguring of the artist is possible and it is urgent.

What is at stake is a confrontation.

Living art signifies action, it is directly connected to deciding, it negotiates negation, it sets examples and examines multiplicity. The creator’s art is diametrically situated to that of the viewer, the reader etc. Uniqueness, inspiration, scintillation are now the empty signifieds of the dominant spectatorial conception of art. They are the narratives which uphold the ideology of the spectacle. / Art values reality, it is a value investment that reaches as far as the perpetuation of the moment. It renders reality precious in sharp contrast to technique, which disdains it.

The purpose of art is to render human actions valuable, using the means which the current development of the times affords.

4.

I loathe the stock values of the industry: “originality”, innovation, novelty and alongside those, their main instances in the 20th century – work camps, concentration camps and the atomic bomb.

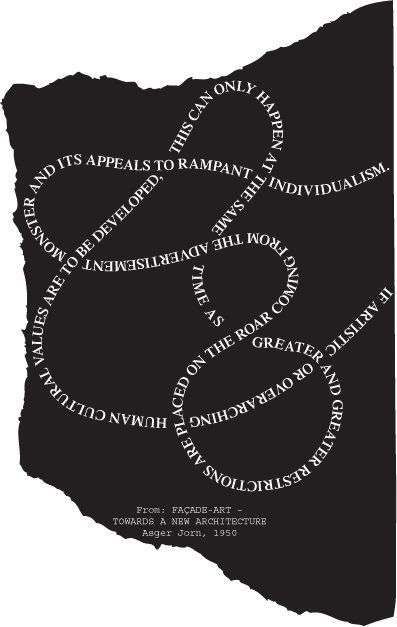

Artistic experiments continue to exist, whereas an experimental field no longer does. That is being endlessly crushed between commercial pusillanimity, resentful controversy and academic hypocrisy.

More and more artists find themselves in an unprecedented impasse and are forced to beg the state for certification, become “prize pupils” and go after distinctions from opportunists the world over, presenting their wares to collectors, institutions, residencies and fairs. Forced to respond to the requirement of constant self-promotion, they regularly make fools of themselves and lose themselves in the neurotic need of acceptance by no-matter-whom.

We thus give away the most precious thing of all – our time.

5.

There is no creative-poetic activation except opposite of society. The social human remains man’s most convincing instance. Despite that / the generality of a social life cannot exceed the tragedy of a private life. Social meaning never does supersede individual’s.

The individual’s enmeshment in the contradictions of the real and its overcoming, reappear as one of the main areas of concern of free artists. A fragmented ‘I’ and a fragmented word may only encounter one another in a way that’s exceedingly contradictory and imponderable. No progress is possible without dire consequences.

6.

Artistic organization is impossible and irrational. Art is anarchy. It is a practice deeply antisocial and it resists organization.

The artist is anti-political. His practice refutes social organization.

It consists in the manifestation and renewal of value differences, hence is sharply at odds with the principle of equality. It attempts increments of progress by experimenting with the discreditation of the existent, without moral prejudice and without defined aims.

What the artist shares with those who are likeminded is the sentiment of rebellion which, however, is changed into a vacant stance (devoid of meaning) when (or as) it evolves into extremism. Every avaunt-guard declaration is finally an eschatology from which we ought distance ourselves, the sooner the better.

Enough already with groundbreaking practices.

The artist seeks the ties that bind the world together. In that regard, he has been abandoned to an apparently useless and futile struggle. Persistence is necessary in order to found a cause on nothingness, on the purely contingent, on the irrational, since wordly forces require a spiritual justification of their power. The ideal of the State.

The activity of the artist in relation to that coercion is the activity of the dexterous burglar-saboteur. He gains an overview of the area, assesses the risk, secures an escape route, works fast, minimizes the duration, blows everything up.

7.

Art is what is discontinuous within the continuity of the world’s narrative. It is an ensemble of incisions and methods whose horizon is the autonomy and freedom of the individual and whose field of development is social becoming.

It is proof of the individual capacity for free action and simultaneously the main means of increasing public nervousness and releasing man’s available energy tensions. Tolerance is the one thing not tolerated in the artistic field.

The construction and projection of a theory of the restrictions, rules, principles or causes for which I create, in short, a narrative of the process of the artistic work, has a soporific effect and, in any case, it lapses into a didactic subterfuge, an educational obstacle on the way to autonomy, to the understanding of social requirements and possibilities of the times. Every promotion of the process ends in pathetic introductions and afterwords.

8.

Availability is the precondition of self-ordained creative activity. Those who have everything to gain and nothing to lose are the artists who are today virtually the only group in the population who retain their total availability unaffected. Several ruses have been enlisted to rescind that availability the outcome is that, even if “artistic production” keeps up, it is void of artistic value.

For the artists who have preserved their free availability and creative capacity, life becomes increasingly dire. One might speak of homelessness. Whoever today chooses or answers the call of free creation, must be prepared in advance for relentless persecution, malignment, pressure and, in the event these do not have the desired effect, lawsuits.

9.

We do not pick our time even if we transform it.

Europe’s cultural production is strictly separated from its society and functions as a central propaganda machine of reality reversal. It is an obscurantism claiming to be an enlightenment. Academia as a movement remains a staunch enemy of art and of the artist. We do not oppose the schools of craft production nor the Fine Arts academies. They are not our concern.

The free artist is a professional amateur. The spirit of amateurism does not signify one is a complete autodidact but, rather, the capacity to overcome one’s knowledge in favor of a new innocence, a new zero starting point or a sense of utter ignorance. Art never provides values but consists in the power necessary to affect and release the ones existing. That is to say, it is a destroyer of human quality and integrity and it is this destruction of perfect integrity that is experienced as beauty. The secret of art consists in the simple fact that it is more beatific to give than to receive but this beatitude hinges on a voluntary offer, on the sense that the offering is considered to be surplus, an abundance and is not motivated by a sense of duty. Art destroys, subverts, liberates.

Oblivion remains our foremost passion.

10.

Only changes attract people’s attention. Creating changes is what is called a game or a variation. To establish a field that operates on the principle of necessity is to annul the possibility of a game or of variations within it.

The game may be considered the foundation of what we call fine arts and this is due to the attraction exercised by the risks to which we are exposed in the course of the game, an attraction requiring an optimal concentration of skill to attain optimal performance.

Only through high stakes may optimal performances derive.

11.

Loneliness is lying in wait for the artist.

During the game, during the concentration of individual skills there are many dangers. The “game” is a closed off narrative.

By contrast to the vastness of the real, it starts, it ends, it has rules.

Life goes on.

In 1964, Asger Jorn was awarded a Guggenheim Award including a generous cash prize, by an international jury assembled by Lawrence Alloway. The following day Jorn sent this telegram to the president of the Guggenheim, Harry F. Guggenheim : GO TO HELL BASTARD—STOP—REFUSE PRIZE—STOP—NEVER ASKED FOR IT—STOP—AGAINST ALL DECENCY MIX ARTIST AGAINST HIS WILL IN YOUR PUBLICITY—STOP—I WANT PUBLIC CONFIRMATION NOT TO HAVE PARTICIPATED IN YOUR RIDICULOUS GAME.

KLARA LIDÉN, PILLAR HUGGER

In 2012, when I applied for a so-called mediators grant to support a curatorial research into Jorn’s writing and thinking I played around with the idea to look at the work of the Swedish-born contemporary artist Klara Lidén (1979) through the lens of Asger Jorn’s ideas on vandalism. Now, 4 years later, Zoë Gray, Senior Curator at the centre for contemporary arts Wiels, in Brussels, gave me the incentive to finally do so for a lecture in the framework of the exhibition Klara Lidén: Battement battu (29.10.2015 – 10.01.2016). The text is a slight adaption of the lecture that I held on January 6th, 2016 at Wiels. I would like to thank Zoë Gray, and I would also like to thank a range of art historians and other Asger Jorn specialists whose perspectives have been highly informative to this lecture including Ruth Baumeister, Helle Brøns, Niels Hendriksen, Karen Kurczynski, and Peter Shield.

Asger Jorn

Let me introduce the first one of the protagonists of this lecture in more detail: the Danish experimental artist and thinker Asger Jorn (1914-1973) was one of the founding members of the Danish Høst group (1934-1950) and the associated magazine Helhesten which he founded (1941–44); the international experimental Cobra group (1948-1951); the Movement International for an Imaginist Bauhaus (1953); and the Situationist International with among others Guy Debord (or SI, 1957–1972), and the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism (1961-1965).

To Jorn’s own way to go about we could certainly attribute ‘vandalistic’ tendencies: he would cut out images, scribble or underline passages in his own books (as well as in the books of others), he would buy bourgeois, academic style Sunday school paintings at the flea market and alter them, he would for several years in a row go back to the house of the collector of his largest painting to continue altering the painting because the buyer had made a comment about the work perhaps ‘still missing something’, he would run a scooter over a large clay relief leaving the tire track visible in the end result, and he would tear down tick layers of posters in the streets of Paris to ‘décollage’ them.

Even the way that Jorn used photography in for instance his book Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados (1964, on mediaeval graffiti on churches in France) has been labelled ‘vandalistic’ for the continuous disconnection of the photographs from historical chronology in favour of a purely visual order (Niels Hendriksen).

Asger Jorn, Signes gravés sur les églises de l’Eure et du Calvados, 1964

Klara Lidén

Protagonist number two is the Swedish artist Klara Lidén (1979) who lives and works between Berlin and New York. Lidén works with performance, interventions, video, installation and sculpture. Her main interest is an exploration of the physical, psychological and social limits and conventions of both public and private space; the street as an endless source of inspiration and action; an obsession with recycling and transforming urban materials; physical gesture and use of the body. She has recycled waste packaging into makeshift hideaways, turned old posters into paintings, along with many other kinds of creative vandalism.

Like Asger Jorn’s décollages, Lidén’s Poster Paintings series consists of layers of glued-together advertisement posters taken from the streets, but in contrast to Jorn who reveals so to speak hidden compositions, Lidén’s sole addition is a white top sheet. A series of spray-paint works on paper by Lidén show traces, prints of everyday life items that the artist finds in her studio or among her personal belongings, including her bike. Again an image that reminded me of Jorn, of his clay relief.

Overview of various works on paper with spray paint by Klara Lidén, exhibition detail, Wiels, Brussels, 2015.

Lidén’s photograph Bowery (2012), showing a figure that has climbed on to a street sign at an intersection; and Column Monkey (2013), in which we see how she ascended on the pillar of a deserted building in an urban zone reminded me of images in one of the publications of Jorn’s SISV.

Pillar-breakers or pillar-huggers at Lund Cathedral, photograph by Gerard Franceschi in Jorn’s publication “Skånes stenskulptur under 1100-talet” (12th-Century Stone Sculpture of Scania), 1965.

JORN ON VANDALISM

Not only did Jorn display a ‘vandalistic attitude’ within his own art practice, throughout his writings he also theorized on the concept of vandalism but of course, the concept is part of a web of other notions, and I decided to simply take a few of these as a starting point for further analysis and speculation.

Value

In relation to the notion of value I would first like to bring up the vocabulary of the Situationist International, which happens to be frequently mentioned in relation to Klara Lidén’s work – especially the notion of détournement. Détournement is usually translated into English as ‘diversion’. An English translation of the Situationist publication Détournement as negation and prelude[1] (originally published in French in 1959) says: “Détournement, the reuse of preexisting (artistic) elements in a new ensemble, has been a constantly present tendency of the contemporary avant-garde, both before and since the formation of the SI. The two fundamental laws of détournement are the loss of importance of each detourned autonomous element — which may go so far as to completely lose its original sense — and at the same time the organization of another meaningful ensemble that confers on each element its new scope and effect.”

Artistic examples of detourned expression include Jorn’s previously mentioned modifications, his altered Sunday school paintings. As Karen Kurczynski writes in The Art and Politics of Asger Jorn, with these kind of works “Jorn expressed an overt critique of the social exclusivity of high art from classicism to modernism and beyond.”

Asger Jorn, Modification with Brittany Woman, 1962. Collection Cobra Museum of Modern Art, long-term loan by Karel van Stuijvenberg,

On the occasion of an exhibition of these type of paintings, Jorn wrote: “In this exhibition I erect a monument in honor of bad painting. Personally, I like it better than good painting. But above all, this monument is indispensable, both for me and for everyone else. It is painting sacrificed. This sort of offering can be done gently the way doctors do it when they kill their patients with new medicines that they want to try out. It can also be done in barbaric fashion, in public and with splendour. This is what I like. I solemnly tip my hat and let the blood of my victims flow while intoning Baudelair’s hymn to beauty.”[2]

But despite this colourful remark, Jorn’s ‘vandalistic’ approach was never aimed at one-dimensional disrespectful destruction. This is also illustrated well by something else Asger Jorn said about his modifications in the same text:

Be modern / collectors, museums / if you have old paintings / do not despair / Retain your memories / but detourn them / so that they correspond with your era. / Why reject the old / if one can modernize it / with a few strokes of the brush. / This casts a bit of contemporaneity / on your old culture. / Be up to date / and distinguished / at the same time. / Painting is over/ You might as well finish it off / Detourn (détournez) / Long live painting.

Contemporary art historians tend to think of the modifications as re-valuations, or as “progressive use of tradition”. As Helle Brøns points out Jorn fully recognized that the creation of new values by devalorization is only possible where there is something to de-valorise, i.e. where a recognized value already exists. Brøns: “There is a fundamental difference between Debord’s attitude to the détourned material as something losing its significance, and Jorn’s maintaining – in part – its original value.”[3]

An artistic example of the use of detourned expression in Klara Lidén’s work could be the previously mentioned Poster Painting series. The posters lose their autonomy, and the reorganization by the simple gesture of adding a blank top sheet undermines their presumed message. The title of these works make a general reference to painting, the blank top sheet suggest a particular reference to the tradition of the abstract monochrome in modernism, the ‘upgrading’ of street posters to ‘high art’ could (as was the case with Jorn) be read as an overt critique on the social exclusivity of high art.

Below, I will discuss the next point that is also intertwined with Jorn’s thinking about vandalism but that leads to a pointing at some fundamental differences in Jorn’s and Lidén’s respective practices.

Progress

In Jorn’s texts the complete freedom required to create pure experiment, and the transgression of existing modes of thinking and pre-established norms and ideas, are inextricably linked to the notions of progress (and risk). In his text ‘Charms and Mechanisms – upon the role of vandalism in the history of arts’ (published in French in 1958 in his collection of essays Pour la Forme (the first substantial publication within the Situationist International) Jorn also brings up the example of the testing of new medicine (like with the detourned paintings when he speaks about “the blood of my victims”). He uses this example to illustrate the fundamental idea that risk, the notion of loss (or potential loss) are in fact an intrinsic part of progress. “I wager this clear idea”, Jorn says: “that there will never be any progress without tragic consequences. The gamble with life is the origin and the price of all progress.”[4] In other words: all progress is vandalistic and barbaric.

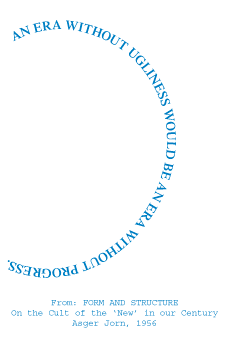

So what else does Jorn’s perspective on progress entail? In Charms and Mechanisms he states that he believes in progress, but that as an artist he rejects “any ethical interpretation of progress understood as moving towards happiness, justice or whatever.”[5] Jorn’s rejection of this interpretation might have been influenced by the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard, whose writings Jorn was very familiar with, and who belongs to a generation of thinkers who, I quote the Finnish philosopher Georg Henrik von Wright: “in the course of the nineteenth century had clearly distanced themselves from the idea of the myth of progress” and who according to Von Wright were “not necessarily pessimistic but in a sombre mood of self-reflexion and questioning of dominant currents of their time.”

Based on this more critical attitude, Jorn’s take on progress is instead, I quote: “(…) simply the feeling one has when one moves forward, on a train, for example, and sees the countryside disappear in the opposite direction. The feeling of progress implies losing something while gaining something else.”[6] “It is only by change, that is to say by movement, that the notion of time is available to us … If there are no events there is obviously no sequence, and consequently no time.”[7] According to Jorn, it is the direct goal of the arts to create these events – it is the speciality of the arts to do so. In his own practice this meant that he always aimed to create what he called “the greatest sensorial significance” by varying and diversifying processes.

Despite his rejection of the idea that progress necessarily implies improvement, one of Jorn’s motivations to write Charms and Mechanisms stems from a concern over the declining power of the human race to evolve. In our struggle for reason, we are abandoning this power, Jorn says, by “giving up all irrational or artistic activity in the sphere of the imagination” – whereas it is exactly this activity that generates new knowledge, artistic knowledge[8] (which Jorn also refers to as “comprehension without recognition”).

The Myth of Progress

Klara Lidén has been preoccupied with the notion of progress as well, as is illustrated in the titles of some of her works and the title for her solo exhibition, at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin in 2014: The Myth of Progress. She took the title from an essay by the aforementioned Finnish philosopher Georg Henrik von Wright (1916 – 2003).

As Jacques Bouveresse points out in his article ‘Wittgenstein, von Wright and the Myth of Progress’[9] Von Wright wasn’t critiquing progress itself, but critiquing the idea that progress is unbounded and everlasting, natural and necessary, and that this type of progress is inscribed in the nature of human beings as a species. Bouveresse quotes Von Wright: “(…) we may seriously wonder whether the idea of unlimited progress, understood in such a way, is not liable to enter into contradiction at some point with the natural species itself, which necessarily implies an environment and living conditions which must also remain, at least to a certain extent, natural, and cannot be transformed in any way we could like and without any limits.”

In contrast, Asger Jorn is aware of the risks that come with progress (its ‘vandalistic’ aspect), but accepts the risk, while maintaining a desire for, or a belief in progress. In his artistic practice this translates into an experimental working method based on bringing about variation and diversification. Large parts of his artistic output, consist of taking existing elements and altering them, resulting in a new objects that now say something else. Think of his modifications, or of his décollages.

In comparison Klara Lidén, who we could argue lives in a world that starts showing the actual consequences of unlimited progress, seems to add just the minimum to a world already overloaded. There is a stronger focus on conceptual, minimal gestures such as with the stacked pieces of asphalt, or with the Poster Paintings: when Klara Liden takes a thick layer of posters from the street and alters it, strictly speaking, she doesn’t add another/her own voice, she rather mutes the original message.

Or, where Lidén leaves a modest bike tire trace on a piece of paper, Jorn leaves behind the noisy tire track of a scooter on the largest clay relief in Europe (27 meter); where Jorn has written hundreds of texts and engaged in public discussions, I can only find a modest amount of interviews by Klara Lidén, and where Jorn co-established various artist groups all trying to raise their voice, always discussing and debating, also amongst themselves, we see Klara Liden on her own, or as a solitary individual even if amongst a group of other people (such as in her well-known video Paralyzed, 2003, in which she does a wild, uninhibited dance on a commuters train in Sweden). In conclusion, I would like to speculate that it is perhaps Jorn’s and Liden’s respective perspectives on the notion of progress are accountable for these kind of differences in their artistic output.

I will now jump to the last notion that is closely related to Jorn’s ideas on vandalism, which is the notion of resistance.

Resistance

From an intellectual point of view Jorn was interested in vandalist expressions as acts of resistance against the reigning order: the graffiti that he found on the churches in France was supposedly made by Viking “vandals”, and the book 12th Century Stone Sculptures of Scania is emblematic for the SISV approach by demonstrating a subtle subversion of the iconography of power. This aforementioned book which includes the image of the pillarhuggers/breakers traces the infiltration of a non-Christian iconography of beard-pullers, double-heads and pillarhuggers in the decorative programs of churches built in the aftermath of the annexation of Scania by the recently converted kingdom of Denmark around the year 1000.

The subversion of existing hierarchies and power relations runs through Jorn’s thinking and practice as a red thread. In Charms and Mechanisms, when Jorn speaks of what distinguishes the artist from “his adversary” he characterizes the artist as the one with conscious opposition to the reigning order in life and places what the calls the “grotesque folly of a too probable existence played out in advance” in direct opposition to the “pure desire for the unexpected, the thirst for surprise, the longing for the absurd, and the attraction of the abnormal, in short, towards diversion, amusement, the ‘dérive’.[10] And a bit further on he writes: “all artistic structurations are just different forms of networks of resistance against movements. (…) all we need to point out here is that artistic currents cannot, as imagined by politicians, serve directly to unify and accelerate general social movement. On the contrary, as counter-currents they are engaged in enriching, diversifying and enlarging the importance of an existing movement by diverting it.”[11]

What speaks from these citations is Jorn’s love for dialogue between a plurality of voices, which is not only part of his thinking, it is also expressed in the collaborations that he was always looking for. To Jorn the dialogue with others, whether harmonious or conflicting, was never supplementary or subsequent, but foundational to his practice and the way he dealt with art as a public phenomenon. Within these collaborations Jorn was fiercely opposed to watered-down consensual results. He believed that consensual strategies needed to be avoided in order for everyone involved to give their very best. The dialogues that Jorn was looking for, were of a more polemic, combative nature. In contemporary terms we could perhaps even speak of Jorn’s attitude as agonistic. “Within agonistic theory disagreement and disputation as deemed necessary, rather than negative components of political and social life”, they are considered “constituents that are at the foundation of an active, vigorous instantiation of citizenship. Within this conception of the public sphere no boundaries or borders can remain unchallenged.”[12]

In conclusion we could say that Jorn, who despite his statement about the rejection of an ethical interpretation of progress, is still driven by the idea that artists and architects could potentially make a difference, testifies of a resistance that is so to speak ‘loud’. In contrast Lidén’s seems a mute resistance, perhaps even totally devoid of risky dreams of a better world. As Helen Molesworth writes in an excellent article in Art Forum when discussing Lidén’s practice: “the artist at work is imaged as silent, sullen, solitary, and quite possibly self-defeating.”[13] Molesworth speaks of a “muted, nearly autistic sensibility” in relation to Lidén. But what does that imply in regards to the notion of resistance, of critique in her practice? Obviously she is not looking to argue, to engage in an active, vigorous instantiation of citizenship ….

Perhaps we should take the term postcritique, a notion that was brought up by Helen Molesworth in the same text, into consideration. The way I understand the term postcritique (though admittedly based on very limited knowledge), suggests that Lidén belongs to a generation that is critical of universal normative principles. A generation that as such is not primarily concerned with these, whereas nevertheless looking for the possibility of critical resistance to moral and social ills. However, as David Couzen Huoy points out in his book Critical Resistance – from Poststructuralism to Postcritique the type of resistance, the in-your-face refusal, exemplified by the famous students uprisings in Paris in May 1968, in which the Situationists International played such a preponderant role (to some extent their political perspective and ideas fueled such crisis), has been replaced by another. The ’68 motto “we are realists, we demand the impossible” nowadays simply means “to resist globalization of capitalism even when one does not have a better alternative to offer” (here Huoy sketches the perspective of Slavoj Zizek).

This perspective might offer an explanation of why Florence Waters in a 2010 review in the Telegraph on Klara Lidén’s solo show at the Serpentine Gallery felt compelled to write that it: “(…) is the knowing futility of Liden’s gestures that separates her from the previous generation of art vandals.” And that, “Unlike her forefathers, Liden’s message is too suffused with irony to be political. She seems, almost, to be poking fun at her predecessors (…) for the naivety of the idea that art would be grand enough to really change anything.”[14] Also Helen Molesworth discusses some of Liden’s works as “the staging of what may be the central dilemma of today’s emerging artist: the futility of being one in the first place.” She writes: “And spending time with her work, one realizes that the twentieth-century paradigm of art’s utopian aspirations is not what’s at stake. Lidén offers blankness—and its aural handmaiden, muteness—less as a critique or a way out than as a condition, less as a program than as a given (reduce, reuse, recycle). In her work, I sense a tacit acknowledgment that the jig is up, that being an artist is just another way of getting by, a coping strategy for living under late capitalism.”[15]

Perhaps this ‘just another way of getting by attitude’ (I’m sure that I’m making it sound more negative then Molesworth intended) is a justified observation. I can see why it would be. I can then also see how this attitude is ground for critique that was expressed in a review in Frieze of a group show in which Lidén was participating. In the article some of her work, as well as that of some other artists, was criticized the following way, I quote, “the pointing towards resistance and subtle undercurrents of violence became the objects of aesthetic contemplation.

This was palpable in Klara Lidén’s series of framed black and white photographic prints, including Untitled (Down) (2011) and Untitled (Monkey) (2010). In these images, a distant person traces alternative routes through the city, up concrete pillars and down manholes. These works did not merely speak of an aesthetic of revolt, but also of the fetishization of resistance.”[16]

But I am having a hard time to buy the ‘just another way of getting by attitude’. Perhaps I simply find it too depressing, but I also guess that there are much much easier ways of getting by then being an artist. And funnily enough, the works criticized in Frieze magazine, are pretty much the same works that led Darran Anderson in a passionate and positive review of Lidén’s solo exhibition at IMMA to conclude that she “demonstrates that we can resist through small imaginative acts of revolt, or at least express our alienation.”[17] Anderson brings up the humorous aspect of the work, as well the notion of danger and risk (public ridicule, attention of authorities, physical harm). And he speaks of how in these works, Lidén’s presence in public space communicates that “any attempt at individuality or real interaction with the surroundings will have stern and immediate consequences”. Crucially, Anderson also adds that “Critically, these are unspoken warnings, existing already in our own heads.”

So what perhaps primarily becomes obvious from Anderson’s observations, is that we are not looking at an artist who is ironic up to the point where the work stops being political, or whose artisthood is just another way of getting by. Lidén belongs to a generation that knows too well (to quote from David Huoy’s book) “that domination and resistance are intimately related to each other, that perception of social constraints is itself produced by social constraints, and thus is just as likely to perpetuate these constraints as to escape them.” What seems to be ‘just another way of getting by’ might in fact be a constant struggle, a way to resist the pitfall of not recognizing that “power and domination may (…) be more complex than it appears on the surface, that the social features that are being resisted may produce the shape that resistance takes.” (Huoy uses the example of a teenager who imagines a world without parents is in fact still presupposing the subject identity teenager and therefore the same social organization that is resented).

In that sense we could think of Lidén’s strategies (the muteness, the solitary acts, the ironic humor, the use of her own body) as highly politically informed strategies all aimed to create “latent and subversive relationships to representation” (as Carl Kostyal expressed it in the same Frieze review on a more positive note on Lidén’s work). I would like to think of Lidén’s repeated performance or embodiment of the pillarhugger/breaker (coming from Sweden she might very well know the mediaeval predecessors in the Lund cathedral) as emblematic for her interest in subversive relationships to representation.

With Column Monkey and similar works, Lidén expresses an interest, like Jorn had, in a transformation of the inorganic to the organic function, challenging the fundamental, static character of architecture. And as Niels Hendriksen points out in his article on Jorn’s Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism, things and beings that are in a state of transformation inherently hint at subversive relationships to representation, as they hint at cultic metamorphosis, in which value is mutable, where dragons, fish, and other creatures are turned into princes and princesses who in turn become deer, birds, and ghosts. This conflicts with the Judeo-Christian metaphysical world order that stands above nature and matter, and in which (in Christian iconography) the stability of animal symbols serves to perpetuate societal hierarchies.[18] Unlike Asger Jorn though, Klara Lidén is not only interested in investigating the subversive nature of the representation of metamorphosis: by making use of her own body, she becomes the pillarbreaker.

[1] The full text can be found here http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/3.detourn.htm

[2] Asger Jorn, ‘Detourned Painting’, in: Hvad skovsøen gemte / Jorns Modifikationer & Kirkebys Overmalinger, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, 2011, p. 132-133.

[3] Helle Brøns, ‘The Shock of the Old’, in: Hvad skovsøen gemte / Jorns Modifikationer & Kirkebys Overmalinger, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, 2011, p. 136.

[4] Asger Jorn, ‘Charms and Mechanisms – upon the role of vandalism in the history of arts’, in: Concerning Form – an outline for a methodology of the arts, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, 2012.

[5] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 107.

[6] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 107.

[7] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 108.

[8] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 109.

[9] Paragraph, volume 34, issue 3, page 301-321, ISSN 0264-8334, Available Online November 2011. The full article can be found here: http://dx.doi.org/10.3366/para.2011.0027

[10] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 112/113. Dérive is a mode of experimental behaviour connected to the conditions of urban society: a technique (used by the Situationists) of transient passage through various ambiences.

[11] ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, p. 117.

[12] Rafael Schacter, Ornament and Order – Graffiti, Street Art and the Parergon, Ashgate, 2014, p. 95.

[13] Helen Molesworth, ‘In Memory of Static’, in: Artforum, March 2011, p. 217.

[14] The review can be found here: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/art-reviews/8056879/Klara-Liden-Serpentine-Gallery-review.html

[15] ‘In Memory of Static’, p. 222.

[16] Carl Kostyál, Awaiting Immanence, in: Frieze, Issue 157, September 2013. The review can be found here: http://www.frieze.com/issue/review/awaiting-immanence/

[17] Darran Anderson, ‘Klara Lidén: The Myth of Progress’, in: Studio International, 18/11/2013. The review can be found here: http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/klara-liden

[18] Niels Hendriksen, ‘Vandalist Revival: Asger Jorn’s Archeology’, in: Asger Jorn, Restless Rebel, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, 2014.

ALFRED JARRY AND ASGER JORN: THE EPICUREAN INFLUENCE AS SOCIAL ‘SWERVE’, BY KOSTIS VELONIS

Within the framework of my research into Asger Jorn´s writing and thinking I organize public and semi-public sessions with special guests at a variety of venues. The guest´s practice, knowledge, insights, or responses are informative to my research, or steer the direction I take on a particular topic. The sessions also often respond to the context of the hosting institution, or to a specific request. Making the sessions public is a way to share and enter into a dialogue with the audiences.

On January 8, 2016 the session ‘Asger Jorn: Thinking in Threes’ was hosted by Circuits and Currents, the Project Space of the Athens School of Fine Art. Two Athens-based artists contributed to this session. Yiannis Isidorou with a performance-text which can be found in the Public Sessions section of this blog, and Kostis Velonis with the text below.

Kostis Velonis received his Doctorate in architecture from the N.T.U.A University of Athens (2009). He studied Cultural Studies (MRes) at the London Consortium and Visual Arts at the Paris VIII University, (Maitrise, D.E.A). Recent shows (selections 2014-15): This probably will not work, Lothringer13 – Städtische Kunsthalle München, Munich 2015; Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract Art and Society 1915 – 2015, Whitechapel Gallery, London 2014; The Theater of the World, Museo Tamayo, Mexico City; This is not my Beautiful House, Kunsthalle Athena, Athens; No Country for Young Men, BOZAR, Brussels.

As the current conditions in global markets are in a potentially unstable situation the activation of Epicurus’ (341-270 BC) swerve (“Clinamen”) proves to be of some interest, since it introduces us into a mobile and liberating perception of things that corresponds to the risks of the financial hyper-capitalist structure. Epicurus’ positions are firmly opposed to Platonic cosmogony, given that in Plato’s only text on nature, Timaeus, real nature is a perfectly organized structure consisting of geometrical elements, such as spheres, pyramids, cubes, etc. In many ways, quantum mechanics, which describes the behavior of matter on molecular and atomic level, can be interpreted as a continuation of the atomic theory expounded by the philosophers of Atomism (Democritus, Leucippus), of which a late proponent, during the Hellenistic period, was Epicurus himself. The philosopher from Samos tried to relate physics and cosmogony with human nature. We would have to wait many centuries until modern physics confirmed the ancient materialists’ speculation on the atomic composition of matter.

Modern physics explains matter recognizing that atoms move in unpredictable directions. Epicurus idea of continually moving atoms that swerve (clinamen), following the inclination of a fundamental randomness, is already confirmed by the history of the discipline of quantum physics.

Lucretian deviation

In short, according to Epicurus, there are only two fundamental elements in the universe: atoms and void. The latter considered by Epicurus as necessary for the movement of bodies. His Roman descendant, Lucretius (99 BC-55 BC), in his philosophical poem – a treatise of physics, actually – under the general title On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura), specifies that “…when the atoms are being drawn downward through the void by their property of weight, at absolutely unpredictable times and places, they deflect slightly from their straight course, to a degree that could be described as no more than a shift of movement“.[i]

Lucretius also examines the issue of the swerve of atoms. He thinks that without this slight deviation of atoms from their usual movement, “all would fall downward through the unfathomable void like drops of rain”, and no contact would be possible, no collision among the original elements, and thus nature would never create anything at all. Lucretius wonders: “…if new movements arise from the old in unalterable succession, if there is no atomic swerve to initiate movement that can annul the decrees of destiny and prevent the existence of an endless chain of causation, what is the source of this free will possessed by living creatures all over the earth?”[ii] It is this “natural” deviation that allows a degree of arbitrariness to the universe and thus introduces the idea of contingency.

The principle of indeterminacy appears to be important for the practice of creative expression, as it constitutes a field where human freedom can be exercised. This liberating indeterminacy subverts deterministic conceptions, the causal perception of the world through the tyrannical chain of causes and effects, and, finally, the Stoic idea of an unavoidable – according to a common belief – fate. All Epicurean thinkers agree on the idea of a free will that does not obey to fate; that is, a will that determines our actions, beyond any kind of predetermination.

Modern deviation: Ubu Roi

The Greek origin of deviation could not have been restricted to antiquity, since it touches upon modern scientific assumptions of physics, and all the more so when one attempts at integrating it with the multifarious logic of modernity. Can this volatile condition of matter, and more specifically of atomic deviation, function as a synecdoche in terms of a theatrical and visual avant garde, through formalist formulations no less?

An “oblique” Epicurean “deviation” can be attested in a Promethean personage of modernity, the Symbolist writer Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), as well as in the writings and the visual work of the Situationist Asger Jorn (1914-1973).

In Jarry’s play Ubu Roi (King Ubu, 1896), an inhuman, brutal and overgrown major usurps the throne of the king of Poland. During the whole play, Jarry’s antihero covers his head and body with a large robe, on which there is the design of a lengthy spiral that winds up on his belly. The term invented by the French writer for this spiral is la gidouille, which indeed denotes a spiral, though not in the sense of a strict, linear geometrical construction, but in a more relaxed sense, as if it was, materially speaking, a formerly taut and now dilapidated hose. This figure is identified with Ubu’s protruding stomach.

Alfred Jarry, “Véritable portrait de Monsieur Ubu”, woodcut for Ubu Roi, Paris, Éditions du Mercure de France, 1896

It is interesting to note the relation between Ubu’s body architecture, his gestures and the spiral on his robe. The spiral on Ubu’s belly alludes to the qualities of Clinamen – that is, to deviation from a straight line, to deviant movement. It could be the graphic illustration of an atom’s course in the void, an atom that has completed an elliptical orbit and now springs to infinity, deviating from any calculation imaginable.

Ubu, the ambitious major, does not content himself with fate; on the contrary, he follows and asserts his becoming, shaping it in his own way. What matters is how he accomplishes his goals, using base instincts such as passion for crime, an inclination to constant intrigues and all kinds of vices. Can the overgrown Ubu, with his ever-expanding belly highlighted by the spiral design, be a model for nihilist thinkers? Since pleasure is so intrinsically ephemeral, we ‘d better not go without it at all: this could be what Père Ubu has constantly in mind before going on with his next brutal act.

Yet from the point of view of Epicureanism, this is very far from a model of pleasure accompanied by a constant disposition of tranquility, in the sense of the absence of bodily pain and mental anxiety. Thus, one should not confuse real pleasure, as theorized by Epicurus, with the pleasures of the depraved. Within the context of Ancient Greek philosophical schools, Ubu is a Cyrenaic. He is a modern caricature of Aristippus of Cyrene, who taught that the future seems so uncertain that it makes no sense to postpone the moment of a fleeting pleasure. Aristippus reminds us indirectly the logic of Jarry’s hero, through his views that the object of desire and pleasure is irrelevant, and that what matters is just the degree of pleasure and the intensity of the feeling of satisfaction.[iii]

Not only does not Major Ubu, who usurps the throne of the king of Poland, wish tranquility, but he consciously pursues this fleeting pleasure that, for the anti-conformist Jarry, is an ambiguous model / anti-model of himself. In reality, Ubu is the Physics teacher Félix-Frédéric Hébert, in Jarry’s high school in Rennes, whom Jarry used to make fun of, along with his fellow students, in an impromptu marionette theater. The full-bodied professor Hébert incarnates all the negative qualities that young Jarry wanted to criticize, and in the stories of these French teenagers he becomes King Ubu.

Alfred Jarry’s “Ubu Roi”, stage design by Franciszka Themerson, Dir. by Michael Meschke, Stockholm, Marionetteatern, 1964

Jarry himself refers to the word clinamen, which is the Latin version of Epicurean deviation, in his pataphysical calendar, where it coincides with the month of August. In a less cryptic fashion, the Latin clinamen-deviation is used in Jarry’s 1898 novella Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations, as a subchapter to describe a painting machine (“Machine à peindre”).

The painting machine is a metaphor of a conscious spatial deviation from a straight line, which “…like a spinning top, it dashed itself against the pillars, swayed and veered in infinitely varied directions, and followed its own whim in blowing onto the walls’ canvas the succession of primary colours…”.[iv] The painting machine, like a “modern deluge of the Universal Seine” is “the unforeseen beast Clinamen ejaculated onto the walls of its universe”.[v] Clinamen, spreading its colors everywhere, could be a metonymic portrait of Jarry, as well as an illustration, in terms of mechanics, of the conditions of the Universe, where atoms are dispersed from a point of departure towards an uncompromised deviation. In Docteur Faustroll, Jarry finds his real model as the inventor of the science of pataphysics, the “science of imaginary solutions”.[vi]

The ornament and the arabesque of Asger Jorn

Although familiar with the literature and the philosophy of Jarry’s discourse, Asger Jorn, who wasn’t a memer of the College but was who was declared ‘Commandeur Exquis of the Ordre de la Grande Gidouille’ wrote in 1961 an article for the Intellectual political movement L’Internationale Situationniste (IS) where he criticized pataphysics for having the qualities of a religion. But his isolated criticism of Jarry’s pataphysics, which was followed by a commendatory note on the part of the publisher, Mr. Guy Debord, cannot possibly annul the influences that nurtured the generation of COBRA (International group of artists and poets, 1948-1951) and the IS.[vii]

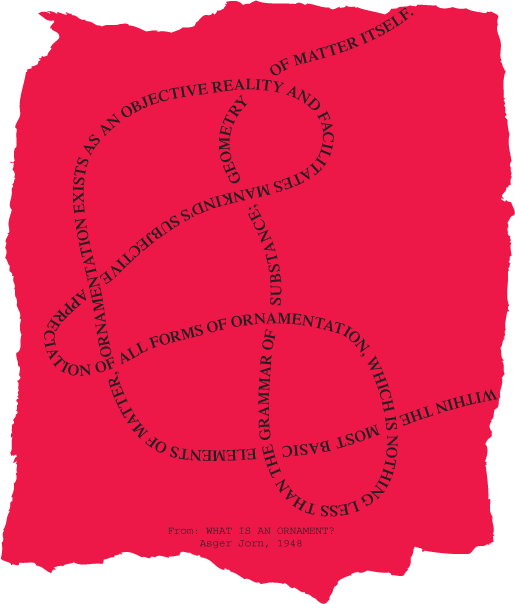

An indication of this influence that shows an Epicurean vein in Jorn’s worldview is found in a text entitled “What is an ornament?”(1948), which reveals how close Jorn is to Jarry’s ideas, yet at the same time how much he differentiates himself from them. In this article, he describes “the wave formation matter”, which is the result of the interconnection between the two substances that are active in mutual movement.[viii] The interaction of the different waves through the formalist interpretation can be attributed to the qualities of the arabesque.

Asger Jorn, page from the essay of Asger Jorn’ ‘What is an Ornament?’ (1948), in Fraternité Avant Tout: Asger Jorn’s Writings on Art and Architecture, 1938-1958, edited by Ruth Baumeister, translated by Paul Larkin (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2011), p.197

From the outset, Jorn gives a summary view of his positions for a “grammar of substance” offered by the philosophy of decoration. More specifically, underneath a picture included in his article, he writes: “An ornament? No, a drawing of the orbital paths of a radium atom”.The physical atom as an ornament and the ornament as a construction that obeys to the laws of physics is an opening to a causality of the deviation of atoms and their reflections towards larger forms, which are destined by nature to move dynamically. The ornament is not programmed to repeat itself unchanged; it changes shape according to the circumstances.

The ingenious Jorn explains colorfully the tendency of matter to result in the organic form of arabesque – similar in this with Lucretius’ clinamen. The shape of the arabesque also comprises Jarry’s gidouille, thus showing immediately an affinity in the treatment of form. Jorn’s descriptions attribute to the arabesques qualities that Epicurus would seek for atoms in the void, spreading everywhere, since anything that moves is destined to take shape, or else to extend linearly as an arabesque in the time-space continuum. At the same time, each arabesque, reacts with other arabesques which have described longer trajectories and “which in turn engage with all that we describe as substances or matter, and of which we only know that there are a myriad arabesque movements – right from the ingenious systems holding atoms and molecules together up to the movement of the planets in space – all circling the solar system’s invisible core”.[ix]

Arabesques can be perceived as the intelligent system of atoms and molecules, and they even explain the movement of plants in space. Accordingly, “we can observe the flowing seas, the evaporation taking place across both land and water, after which it rises to the heavens only to cool once again and condense to rainwater, falling back to the ground so as to join with streams and rivers where the cycle from sea to clouds will start again”.[x] Jorn offers with explicative lyricism the fundamental values of decoration as a life motif. But do arabesques, the quality of movement aside, also have the logic of deviation, as described by Lucretius with regard to the movements of atoms?

Jorn writes: “People rise from their beds in the morning and their pattern of wandering throughout the day describes their own arabesque of footsteps across the earth. They follow the same routes day after day”. And further on: “their footsteps become pathways, which branch out across the terrain and which show where man has left his tracks, and then others go along the same tracks and these become roadways, reflecting the abundance of life – arabesques in man”.[xi] While this description could be attributed to a thinker that sees behind the phenomena visions that repeat themselves identically in time, following a stringent Platonic logic, the answer is finally given by Jorn himself, when he argues that “static forms … have a tendency to become dynamic, because the presentation of dynamic art is the natural way of things”.[xii]

Jorn’s difference compared with Jarry is that the former tries to find a Cartesian acceptance in the dynamic composition of matter, to formalize the Epicurean deviation with the motif of arabesque, although he is no more able to define the limits of this extension. Lucretius expands generously Epicurus’ wisdom, bringing to mind Jorn’s methodology, regarding the traces of arabesques from the small to the grand scale: “Certainly the primary elements did not intentionally and with acute intelligence dispose themselves in their respective positions, nor did they covenant to produce their respective motions; but because through the universe from time everlasting countless numbers of them, buffeted and impelled by blows, have shifted in countless ways, experimentation with every kind of movement and combination has at last resulted in arrangements such as those that created and compose our world…”.[xiii]

Both Jarry and Jorn try to speak, each one in his own terms, about deviation as a fundamental element of free will, which cannot but reflect the Epicurean view of the formation of the Universe. Movements with no connection or movements that deviate from their expected precise recurrence, thus defining what we call contingency, constitute Jarry’s way of philosophizing, through Dr. Faustroll, as well as his nihilistic caricaturizing, through the lame materialist major Ubu.

In the end, if deviation in the sense of declinatio or clinamen corresponds, in terms of social history, to a deviant course, the inclination of which is translated into the subject’s free will, both Jarry, with the blatant destructivity that runs through his writings, and Jorn, with his insistence on an experimental and anarchic creativity, seem to substitute for the claim of an “intelligent design” or the traditional view of God’s omnipotence the subversive qualities of matter. Both expound, though in different ways, a modern-day paganism, compelled by “the presence of a distinct boredom”, going against the supreme will of a god, a doctrine, a predictable existence. Jorn, in particular, advocates“the pure desire for the unexpected, the thirst for surprise… the inclination to difference… the flânerie”.[xiv]

Epicurus’ wisdom is of vital importance for a “deviant” freedom in existential terms. Since all cosmic order springs from this deviation, even the concepts used by the pataphysicians can be moved away from the pragmatist restraint of language, especially if one thinks of Jarry’s exuberant neologisms.[xv] Empirical functions such as a sudden collapse, a violent breakup, a change of course-dislocation, reconstruction or the paradox of love help us, among many others, understand how the Epicurean swerve in physics and philosophy can have an immediate impact on the world of human relations.

[i] Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (De Rerum Natura), translated, with an introduction and notes by Martin Ferguson Smith (Indianapolis & Cambridge: Hackett, 1969), Book II, 216.

[ii] Idid., Book II, 254.

[iii] Despite the similarities between Epicureanism and Cyrenaicism, these two schools constructed very different systems of thought. See Jean Paul Dumont, La philosophie antique (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2003), and W. Windelband-H.Heimsoeth, Handbook of History of Philosophy [Enchiridio Istorias tis Filosofias], Greek translation by Ν. Μ. Skouteropoulos (Athens: ΜΙΕΤ, 1991).

[iv] Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations (Paris: Charpentier, 1911). I quote here the English edition: Alfred Jarry, Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, trans. by Simon Watson Taylor, Introduction by Roger Shattuck (Boston: Exact Change, 1996), p. 88.

[v] Jarry, Exploits & Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, op. cit., p. 88-89.

[vi] “Pataphysics … is the science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments”. Ibid., p. 22.

[vii] Asger Jorn, “La pataphysique: Une religion en formation”, Internationale Situationiste 6 (August) 1961, p. 29-32; included in Pataphysics: A Useless Guide, by Andrew Hugill (Cambridge, Mass. & London: The MIT Press, 2012).

[viii] Asger Jorn, “What is an Ornament?” (1948), in Fraternité Avant Tout: Asger Jorn’s Writings on Art and Architecture, 1938-1958, edited by Ruth Baumeister, translated by Paul Larkin (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2011).

[ix] Jorn, “What is an Ornament?”, op. cit., p. 207

[x] Ibid., p. 207.

[xi] Ibid., p. 207.

[xii] Ibid., p. 203.

[xiii] Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, op. cit., Book I, 1008.

[xiv] Asger Jorn, ‘Charme et mécanique, sur le rôle du vandalisme dans l’histoire des arts’, in Asger Jorn “Pour la Forme. Ebauche d’une méthogologie des arts”, Paris, Internatioanle situationniste, 1958. English translation ‘Charms and Mechanisms’, in “Concerning Form”. An outline for a methodology of the arts”, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, 2012.

[xv] It is interesting to note the deviation searched by Michel Serres in the field of language, when he argues that every language is a unique seed, an original distribution of parasites. He even dares to oppose consonants and vowels in order to convey the necessity of deviation. The ideal example is Ubu’s famous “Merdre” instead of “Merde” at the beginning of the First Act of Jarry’s play. Here is Serres’ argument: “Sometimes winds, breaths, composed together incline toward each other without the intervention of valves or consonants. Oui is a coil, a tress of voice. A bit free, a bit loose, undone, without the anguish of strangulation. Oui without the swarming parasites. Oui in the wind of the Paraclete. Oui in the turbulent tresses of the river. Oui finally works itself loose [se desserre]”. Michel Serres, The Parasite [Le Parasite (Paris: Grasset & Fasquelle, 1980)], trans. by Lawrence R. Schehr (Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982).

AUTHENTIC IRONIES

The text below is an interview that was conducted with Karen Kurczynski in May 2015. Karen Kurczynski is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA and author of the recent publication The Art and Politics of Asger Jorn – The Avant-Garde Won’t Give Up, Ashgate, 2014. A slightly different version of this interview is published in the framework of the Art in Context Programme of the Rietveld Academy, Amsterdam in collaboration with the Cobra Museum for Modern Art. The theme for 2014/2015 was ‘laughter’.

HdB: The Danish experimental artist and thinker Asger Jorn (1914-1973) is well-known for being one of the co-founders of the postwar experimental artists’ group Cobra (1948-1951), and the Situationist International (SI), a movement of artists and intellectuals who strove to achieve social change (1957-1972). Many of those who study Jorn’s oil paintings, etchings, lithographies and other work, will find themselves smiling or even laughing about his puns and parodies, ironic or sometimes tongue-in-cheek humor. In your recent publication The Art and Politics of Asger Jorn: The Avant-Garde Won’t Give Up, Ashgate, 2014, the chapter ‘Authetic Ironies’ discusses the critical and expressive operations of Asger Jorn’s mature paintings, including parody. Here, you identify irony, parody and related strategies as a key element to understanding Jorn’s work, as “foundational to the social nature of Jorn’s aesthetic as a whole …”. Are you aware of previous art historical texts which attribute a similar value to Jorn’s ironizing (including self-ironizing)?

KK: This is an interesting aspect for me to consider now, as I work on an exhibition on Cobra for the NSU Art Museum in Florida (which will end at the Cobra Museum). Because Cobra was not interested in irony at all—or at least, that is what Christian Dotremont writes in one of his key texts, “Par la grande porte” (1949, in a catalog from Colette Allendy Gallery): “They are against ironic painting, which actually tries to express the organic joy of the universe, the historic joy of the world of 1949, but which is ashamed and which trims down the aesthetic impulse […] with an elegant little intellectual penknife.” Jorn too was more interested in authenticity in the Cobra years: he associated irony with the ruling class in his large c. 1947 manuscript “Blade af kunstens bog.” He then explored irony along with humorous strategies more and more over the course of the 1950s. In fact he was always interested in humor in art and in writing, co-authoring a parodic article on a Functionalist named “Everclean” in 1948. Already in his 1952 text Held og hasard, a very Nietzschean text, he rejects the idea of authentic expression. Then by the mid-50s, he openly espouses irony and “lying.” Historiographically, this is precisely the moment his art work begins to be celebrated on an international stage. The critics and curators like Werner Haftmann who wrote about it, however, emphasized it as a return to angst-filled expressionism. Contemporary critics especially in the US, where Jorn’s work is less well known, have continued to dismiss his work as expressionist (or worse, neo-expressionist—ironic and therefore empty) until very recently, after 2000. There are not many art-historical texts that place a high value on irony per se or self-ironizing in Jorn’s work until very recently, when suddenly that issue is becoming ubiquitous. I can’t think of any writer or curator who took his irony seriously until the 21st century, and now I can’t think of any who don’t take it seriously. Those who knew Jorn personally, like John Lefebre and Lawrence Alloway, certainly commented on his humor. It is really the writers you and I know now, our colleagues like Helle Brøns and Axel Heil, who are bringing this aspect into sharper focus today. It’s also related to the evolution of art historiography in general. Jorn (and Cobra) were not taken seriously because their work wasn’t perceived as “serious”—one of the most important key terms in postwar movements like Abstract Expressionism—so writers like Haftmann and Guy Atkins had to present his oeuvre as a serious engagement with major artistic themes. We are in a very different, much more interesting, moment now when artists contribute more writing on art and have helped influenced art critics and historians to recognize the importance of humor and play.

HdB: Irony and parody could be looked upon as a highly self-defensive modes, allowing someone to avert responsibility, to be indirect. However in the title of your chapter the words ‘ironies’ and ‘authentic’ are happily married. This seems to be a contradiction in terms but reading the chapter reveals that you locate the actual criticality and complexity of Jorn’s strategy in the dynamics between both elements. I would be curious to learn more about your perspective on the development of these dynamics. The ‘Authentic Ironies’ chapter discusses parody as a critical operation mostly in relation to work from the end of the 1950s into the 1960’s but (as you also mention) the concepts of irony and artifice are part of the development of Jorn’s aesthetic theory from the Cobra period (1948-1951) onwards. May I ask why you felt it was necessary to make this chronological distinction?

KK: The chronological distinction is really just part of the structure of the book, which focuses each chapter around a theoretical issue (in this case, expressionism and irony) combined with a particular temporal and artistic focus (in this case, Jorn’s mature painting ca. 1957-62). Jorn is interested in humor and play in art from the beginning, from his 30s Miró- and Klee-inspired works onward through Helhesten and Cobra. But I focused on different issues in my accounts of the earlier periods. Also, as I just mentioned, Jorn’s humor and irony come out much more explicitly in his late 50s and early 60s work than at any other period. Each chapter of my book has a title which is a deliberate contradiction, an oxy moron, in a Jornian spirit. It’s the clash of Jorn’s irony in a postwar age so obsessed with authenticity that gives his work such interest, and his position seems newly significant to us now as artists are returning to issues of abstraction and gestural painting but in an extremely sophisticated and sometimes overtly political way, combining abstraction and expressivity with some of the irony associated with pop art, appropriated imagery, and now digital mash-ups—when in the 50s and 60s those two approaches were strictly separated by generation. Recent artists are more interested in combining the best of both generations—the spontaneity and human element in the gesture, but without making it too specialized or spectacular; the humor and sophistication of using appropriated imagery but without it being too easy or celebratory. Jorn’s work does all of this. Today we have a much more sophisticated, “situational” understanding of identity and authenticity in the internet age, and new recognition of the importance of play in the era of video games and “gamification,” that I think makes Jorn’s work seem prescient and newly relevant.

HdB: The following question I have appropriated from a conversation with Jouke Kleerebezem, one of the tutors of the Rietveld Art in Context programme. He was wondering if we could touch upon the type of ambiguity that typifies humor in general, making the ‘laughter’ that results from it an acquired taste, always debatable between those who differ in their sense of humor. So then I wondered if you think Jorn shot himself in the foot every once in a while, and whether he perhaps did not care?

KK: Did Jorn shoot himself in the foot sometimes? Yes. Did he not care? No he did not care. His hits were so on target that I think they excuse a lot of misses that would stand out more in the work of an artist whose work was less complex and multifaceted. He always kept moving which is one of the fascinating things about his work and his artistic practice—it was also a source of heartbreak for those around him, from his wives and girlfriends to his kids, who suffered immensely, and his friends and gallerists. In terms of his humor, take a work like Masculine Resistance at the Museum Jorn, and you can see the retrograde gendered assumptions about the interaction of men and women that make its humor sort of fail from my own feminist perspective today (Helle Brøns has written about the gender confrontation in this work). But at the same time, the failure is itself interesting. It has something to tell us about mainstream gender attitudes in Jorn’s day, on the one hand, and it has a very critical message about the discourses of authenticity and transcendence that characterized art in his day, on the other. Its emphatic vulgarity in both how it was painted and the subject itself is a biting critique and a liberating rejection of the abstract painting that was dominant at the time. So it’s not humor as in a joke, which is always socially divisive (some of the best comics are the most offensive ones—Sarah Silverman for example). It’s more like meta-humor because the humor is always embedded in multiple and contradictory discourses. Jorn’s work is humorous in a way comparable to Richard Prince or Glenn Ligon’s “joke” paintings, which repaint a racist or sexist joke on a monochrome canvas, despite their radically different aesthetics. Whether you laugh at the joke is only part of the point—it makes you stand back and start thinking about what it means to laugh at it in different contexts, as well as (and this is key) the fact that the joke is always so culturally specific that it’s immediately outmoded and, well, no longer funny. So even Jorn at his most sexist or short-sighted has potentially important meanings for us. At the same time, just to negate everything I’ve just said (another Jornian move), I think you can also find passages of sheer physical humor in Jorn’s paintings that might be more universal—the way physical comedy appeals to a wider audience. You can also find references to carnivalesque themes and popular humor as seen in earlier painters like Bruegel and Bosch, and writers like Rabelais who Jorn loved. There are many different forms of humor present in Jorn’s work.

Asger Jorn, ‘Le faux rire (image tragi-comique)’, oil on canvas, 1954. Longterm loan by ABN-AMRO to the Cobra Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen. Photograph: Henni van Beek

HdB: In 1954 Jorn made an oil painting that literally depicts laughter: Le faux rire (image tragi-comique) which translates as The Fake Laughter (tragic-comic image). At the bottom of the painting we see a (literally) two-faced laughing character in a slightly awkard, half-reclining position while holding something up in the air with one arm. In the background above the laughing character hovers a smaller, friendly looking face. Although the painting is the representation of a fake emotion it funnily enough simulaneously brings across a genuine emotion, the mix of twisted feelings that potentially come with a fake laugh (discomfort? repulsion?). I would like to invite you to closer examine this painting from the perspective of ‘authentic ironies’. In relation to Jorn’s paintings La double Face (The Double Face) and Le Cri (The Scream) you for instance bring up notions such as multiplicity, clichés of the representation of human emotion, the understanding of complexity of the self as a social situation, and Jorn’s insistence on meaning-production as an active process.

KK: This is a great work to bring into focus the complexity and multiple dimensions of laughter we just touched on. The image strikes me as very grotesque in its combination of comic and tragic—humor and angst—in a particularly puzzling combination. The history of the grotesque from ancient times (when it was called the “monstrous”) to the present, as many scholars have demonstrated, typically combines humor with horror. So it relates to a prominent theme in human culture. We can all think of examples of situations that are horrible or harmful that, when considered at a remove, can also be really funny (though at the time it was still largely taboo in Europe to produce humorous imagery relating to the Second World War—Jorn’s work plays with those taboos only indirectly). This image features not just those two dimensions of tragedy and comedy, but also a third, the question of “fake” laughter. The issue of something fake destroys any notion of authenticity and cuts through any attempt to securely define something. Then, Jorn began his painting Stalingrad, le non-lieu, ou le fou rire du courage, the same year—the first title of that painting was “Le fou rire” (Mad Laughter) and it may or may not have been a reference to history or history painting or the “mad laughter of courage” in an epic battle at that point. It acquired the title Stalingrad a bit later. Jorn loved puns and I think it’s likely that he linked le fou rire and le faux rire together deliberately. Fou being a reference to an authentic expression; faux indicating irony and inauthenticity. What strikes me about this image is that it seems more troubling than funny, so is it about laughter at all? Or really, it’s precisely about laughter rather than explicitly funny. It is about the significance of laughter. Laughter and play are elements that rational society suppresses and they indicate a critical distance, a resistance to power. They are also intimately linked to creativity itself and the ideas of play and experiment so prominent in Cobra. Laughter indicates a double perspective. The main figure is not just laughing, but sticking out his tongue, which is a gesture of childishness, defiance, as well as disgust; a gesture referenced earlier in Cobra and examined in Jorn’s later book La langue verte et la cuite. The material fleshiness of the painting is also striking. Parts of figures evoke blood and bones, the mouth and the tongue, the eyes made grotesque as they multiply and roll in all directions. It’s an image of illness (recalling Jorn’s abstract portrait of his injured cousin Mads in the Silent Myth murals) and madness, so strongly linked to creativity. It’s also a visceral painting that affects us in an almost physiological way. As it was made in Italy, this was part of Jorn’s reaction against the sleekness of postwar design culture and his investigation of ceramics at the time. It’s a great example of his interest in Bachelardian ideas of the “material imagination.” It is grotesque because it fails to cohere as a recognizable group of figures. Instead it conveys the process of signification. Maybe it even conveys the process of creating humor itself, and its flipside, tragedy itself, out of the neutral facts of what happens in the world. There is also a recognition implicit here (but signified by the contradictions inherent in the title) that the process of signification is always social. So what one calls greatness, another calls tragedy, and yet another calls humor.

PILLAR HUGGERS – A WORKSHOP AND EXHIBITION AT OR GALLERY, BERLIN

with Antonis Pittas, Johann Arens, Jay Tan, Klaus Weber, Christoph Keller, Hilde de Bruijn, Shannon Bool, Hadley+Maxwell

January 23 – April 18, 2015

Reception Friday, January 23, 7:30PM

Curated by Hilde de Bruijn, Shannon Bool and Hadley+Maxwell

The Danish experimental artist and thinker Asger Jorn (1914-1973), well-known as one of the driving forces of Cobra (1948-1951) and L’Internationale Situationniste (1957-1972) was a fierce collaborator, always looking for international exchange and discussions, facilitating collective work, magazines, and exhibitions. With great drive and ambition Jorn also wrote numerous books and articles envisioning, from an artistic point of view, ‘the first complete revision of the existing philosophical system’. Jorn believed that art is not derived from an ideology or worldview, but is the direct expression of an attitude towards life, belonging to the fundamental level of work and production. In line with this, Jorn combined in his writings ideas from a wide range of disciplines including politics, physics, economics, philosophy, anthropology, structuralism and art theory. He brought these various interests together via unconventional methods and in a vast variety of forms, in search of a comprehensive theory of art and life.

The architectural figure of the pillar-hugger as it appears in Jorn’s 12th Century Stone Sculptures of Scania1 represents a character whose body has become petrified while attempting to tear down a Cathedral by its vertical supports. A small group of artists have been invited to occupy the position of Pillar Huggers for a one-day visual symposium at Or Gallery Berlin where their work will form the material of their conversation. Transposing Jorn’s definition of a materialist attitude toward making art (as he articulates in the essay ‘What is Ornament’ (1948)) to exhibition-making, the artists are asked to animate the position of the body who, through its transformation into the inorganic, becomes the support for the very same edifice it attempts to destroy. How can we reconcile the compulsion to ornament with a resistance to the compulsion to make an exhibition? Can we avoid the exhibition as monumental decoration by approaching the encounter of and between artwork with the spirit of Jorn’s conception of vandalism and the spontaneous arabesque?

The remnants of the workshop opened to the public at 7:30 pm on January 23, 2015, and have also resulted in the visual essay What is Jornament? (published on this blog). The text is taken from the book Fraternité Avant Tout – Asger Jorn’s writings on art and architecture, 1938-1958. Editor: Ruth Baumeister. Translator: Paul Larkin.

Publisher: 010 Publishers.

—————

[1] The book traces the infiltration of a non-Christian iconography of pillar-huggers, beard-pullers, and double-heads in the decorative programs of churches built in the aftermath of pagan Scania by the recently converted kingdom of Denmark around the year 1000.

About the artists:

Klaus Weber is an artist, who lives and works in Berlin, he has shown extensively in both Europe and the United Sates. He conceives works across a variety of media and spatial units, which are often based on multifaceted technological interconnections and intricately organized production processes. Yet, by purposely manipulating everyday structures, the tracing of deviations and the exploration of the impossible, they undermine the metaphorical and actual power of a functionalist rationality. In doing this, Weber repetitively uses images of nature, and explores the sustainable potential of the untamable in a humorous and anarchic manner. Weber has had institutional solo shows at the Fondazione Morra Greco in Naples, the Nottingham Contemporary, the Secession in Vienna, the Hayward Gallery in London, as well as the Kunstverein in Hamburg. The artist has participated in group shows at the MOCA, Los Angeles, the Mori Museum in Tokyo and at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin. Weber is represented by Andrew Kreps Gallery in NY and Herald St Gallery in London.